Fertility preservation is often not foremost in the minds of women who have been diagnosed with cancer, or even after treatment. However, as cancer survival rates for children and young adults improve, the demand for fertility preservation services will increase. General practitioners who see such patients can play an important role in sharing with them the options available.

INTRODUCTION

Women have a finite reproductive lifespan. A baby girl

is born with all the follicle-containing oocytes she will

have in her lifetime – a finite supply which is depleted

with time as the follicles undergo atresia, and is

completely exhausted at menopause.

In addition, there is also a known decline in oocyte

quality in terms of aneuploidy, related to age-related

instability of the oocyte meiotic spindle. This results

in ovarian ageing and its clinical consequences of

infertility, miscarriage and pregnancy with a Down

syndrome foetus.

WHEN SHOULD MEDICAL FERTILITY

PRESERVATION BE CONSIDERED?

Chemotherapy, pelvic irradiation and ovarian surgery

are iatrogenic factors that are known to accelerate the

natural decline in ovarian reserve. The devastation to

the ovarian reserve and resulting risk of premature

menopause depends on the type of treatment and

its ovarian toxicity, the age of the woman and her

baseline ovarian reserve.

Hence, timely referral to a gynaecologist who specialises in reproductive medicine is crucial when

a reproductive-aged woman requires chemotherapy

or pelvic irradiation, or has undergone ovarian

surgery.

Patient criteria

Women who are suitable candidates for medical

fertility preservation have the following characteristics:

-

Age ≤ 40 years

- Premenopausal

- Has a realistic chance of surviving for five years

- Not pregnant

- Desires to have a child in the future

What Are the Options for Female Fertility Preservation?

1. EGG / EMBRYO FREEZING

Ovarian stimulation followed by the freezing of

mature eggs or embryos is the most established

method of fertility preservation.

Process

The patient self-administers subcutaneous gonadotropins

for about 10-14 days to stimulate multifollicular

development in her ovaries, following

which she undergoes an egg retrieval procedure

under sedation. The patient would be fit to tart chemotherapy as early as two days after

egg collection.

If there is no male partner, the eggs are supercooled

and stored in tanks containing liquid nitrogen.

If the woman is married, the eggs can be fertilised

and the resultant embryo cryopreserved. The

process is essentially similar to in-vitro fertilisation

(IVF), the main difference being that the embryos

are frozen rather than transferred in utero.

Potential risks and complications

The risk of complications is low and includes the

following:

-

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome

- Venous thromboembolism

- Procedural risks associated with egg collection – bleeding, infection, ovarian torsion

Oestrogen-sensitive tumours and breast cancer

recurrence

In patients with oestrogen-sensitive tumours such

as breast cancer, aromatase inhibitors are given

concurrently to alleviate the supraphysiological

estradiol levels during ovarian stimulation. Women

who were given letrozole during ovarian stimulation

had the same risk of breast cancer recurrence as

for those who did not undergo ovarian stimulation, wthout compromise in stimulation results.1

Ostetric and perinatal risks

No increased obstetric and perinatal risks were

found in pregnancies achieved with frozen eggs

or embryos, compared with IVF pregnancies

conceived with fresh eggs or embryos. However,

the long-term health of babies born as a result of gg freezing is not known.

Although the risk of miscarriage and chromosomal

abnormality is related to the age at which the eggs

were retrieved and frozen, egg/embryo freezing

does not prevent the other obstetric complications

(e.g., eclampsia, gestational diabetes, growth

restriction, caesarean section) associated with

advanced maternal age.

For example, a 45-year-old woman attempting to

conceive with eggs that were frozen when she was

at age 30 would have the same risk of maternal

and perinatal complications as women in her

current age group. However, her risk of miscarriage

and chromosomal abnormality would be similar to

that of a 30-year-old.

Efficacy

The success of female fertility preservation is

highly dependent on the woman’s egg quality

and ovarian reserve, which are in turn significantly

influenced by age.

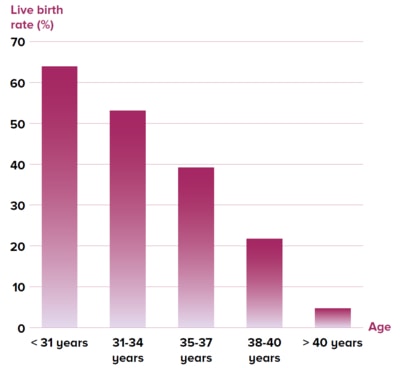

Figure 1 Live birth rate stratified by age after

one complete cycle of embryo freezing in 20,687

Chinese women2

Figure 2 Oocyte-to-baby rate stratified by age3

A large study2 reported the live birth rate after

one cycle of embryo freezing in 20,687 Chinese

infertile women of various ages (Figure 1),while

another study3 reported the oocyte-to-baby rate

for different ages of women (Figure 2).

Besides egg quality, other factors such as smoking,

history of polycystic ovarian reserve and previous

ovarian surgery are also important.

A common misconception is that fertility preservation

is an insurance against future infertility; it is

not. The reality is that live birth is not a guarantee,

and it is more realistic to consider fertility

preservation as offering an extra opportunity to conceive with younger and better-quality gametes.

2. OVARIAN TISSUE FREEZING

Ovarian tissue freezing offers a different approach

to fertility preservation, other than the freezing of

mature eggs or embryos.

A typical cycle of egg freezing allows the retrieval

of a small number of eggs (usually less than

30), whereas the freezing of ovarian tissue with

whole follicles, each containing a single oocyte

surrounded by steroid hormone-producing cells, allows thousands of oocytes to be frozen in one

instance.

Premature ovarian failure is a known adverse

effect of highly gonadotoxic chemotherapy as well as pelvic radiotherapy. As ovarian tissue freezing

also preserves the steroid hormone-producing

cells of the follicular unit, it can restore fertility as

well as the hormonal function of the ovary.

Process

The ovarian tissue is retrieved by surgery, which

can usually be performed laparoscopically. As

most of the follicles in the ovarian tissue are in

the primordial stage, the ovarian tissue needs to

be reimplanted back into the body via a second operation to regain its functionality.

Typical graft sites are the remaining ovary and

pelvic sidewall (orthotopic) and anterior abdominal

wall (heterotopic). Currently, the only way to use

frozen-thawed ovarian tissue is in vivo; in-vitro

methods to retrieve mature oocytes from primordial

follicles are still being researched on.

Unlike in conventional organ transplants, patients

do not need to take any long-term immunosuppressive

medications after ovarian tissue

transplant surgery. This is because the ovarian

tissue that is harvested and reimplanted back into

the body is the patient’s own, thus there is no risk

of organ rejection.

Timing considerations

The lifespan of the graft is very variable, and

depends on the amount of tissue transplanted

and the age of the woman when the ovarian tissue was first removed. Graft survival ranging from a

few months to up to ten years has been reported.4

Given the limited lifespan of ovarian tissue grafts,

transplantation should be postponed until the

patient is ready to conceive or experiences

symptoms of ovarian hormone deficiency.

Efficacy

Ovarian function was restored in more than

95% of cases, within four to nine months after

transplantation. Among women who were trying to

conceive after ovarian tissue transplant, a live birth

rate of about 30% has been reported, of which half

were spontaneous conceptions.5

Ovarian tissue freezing is a relatively new

procedure, and its experimental label was removed

by the American Society of Reproductive Medicine

only as recently as 2019.

Overall, data on the efficacy, safety and

reproductive outcomes after ovarian tissue

freezing is still limited. It is currently considered

an ‘established medical procedure with limited

effectiveness’ that should be offered to carefully

selected patients.6

Indications

Ovarian tissue freezing is currently the only option

for prepubertal girls.

It can also be offered to patients undergoing

moderate- or high-risk gonadotoxic treatment (e.g.,

stem cell transplant, pelvic radiotherapy) or where

egg/embryo freezing is not feasible. For example,

patients who need to start cytotoxic treatment

urgently would not have time to undergo the

ovarian stimulation required for egg/embryo

freezing.

Potential risks and complications

In addition to the surgical complications of freezing

and grafting the ovarian tissue, there are concerns

regarding the presence of occult metastases in

the frozen ovarian tissue and retransplanting the

original malignancy. The risk is theoretical with

careful patient selection, and depends on the type

and stage of cancer.7

| Requires hormonal stimulation – delay in cytotoxic treatment needed | Does not require hormonal stimulation – no delay

in cytotoxic treatment |

| Does not require surgery; procedure (usually

transvaginal) done under sedation to retrieve eggs | Requires surgery (partial or total oophorectomy) performed under general anaesthesia; a second

operation is needed to reimplant the ovarian tissue

when fertility is desired |

| Smaller numbers of oocytes/embryos frozen

(usually less than 30) | Allows the freezing of thousands of oocytes at one

time |

| Mature oocytes or fertilised oocytes (i.e., embryos)

are frozen | Immature (primary) oocytes are frozen |

| Requires assisted reproductive technology | Allows opportunity to conceive spontaneously |

| Does not preserve ovarian hormonal function | Allows restoration of fertility and ovarian hormonal function |

| Risks related to ovarian stimulation and egg

collection | Surgical risks |

| More established method of fertility preservation | Less established method of fertility preservation |

Figure 3 Key differences between egg / embryo freezing and ovarian tissue freezing

3. GONADOTROPIN-RELEASING HORMONE (GnRH)

AGONISTS

Although GnRH agonists are commonly used

during chemotherapy to reduce the chance of

premature ovarian insufficiency, the mechanisms

which underlie this effect are uncertain.

Efficacy

In addition, studies have shown conflicting

results regarding the risk reduction for premature

ovarian insufficiency, with better results seen in

breast cancer patients compared to those with

haematological malignancies.

Finally, a reduction in premature ovarian

insufficiency may not result in higher fertility

rates.8 Very few studies on the use of GnRH

agonists for reduction of chemotherapy-induced

gonadotoxicity included pregnancy rates as an

end-point, thus evidence for the fertility-preserving

potential of GnRH agonists is scarce.

As such, international guidelines are unanimous in

stating that because of the limited evidence, GnRH

agonists should not be considered an equivalent

or alternative option for fertility preservation and

should not be used in place of proven fertility preservation methods.8

Patient background

A 24-year-old lady with early-stage Hodgkin’s

lymphoma was referred for fertility preservation.

She was single and virgo intacta with a good

ovarian reserve. She had regular periods with no

known gynaecological issues. The patient was planned to start urgent

chemotherapy with doxorubicin, bleomycin,

vinblastine and dacarbazine (ABVD).

Assessment and counselling

The patient was offered ovarian tissue freezing

as there was insufficient time for the ovarian

stimulation needed for egg freezing.

She was reviewed by the anaesthetist prior to

surgery and was assessed to be low-risk for

general anaesthesia. In addition to the operative

risks, the patient was also counselled about the

risk of ovarian metastasis and reimplantation

of the original malignancy with ovarian tissue

grafting, although the risk is small with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Fertility preservation and chemotherapy

She underwent laparoscopic unilateral oophorectomy

and made an uneventful recovery from

the surgery. Chemotherapy was started two days

post-surgery. GnRH agonist was started on the day

of surgery and continued throughout the duration

of chemotherapy to reduce the risk of premature

ovarian insufficiency. |

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES FOR GPs

As cancer survival rates for children and young

adults improve and patients are looking to enhance

their quality of life after cancer survival, the demand

for fertility preservation services will increase.

General practitioners may occasionally see young

women who have been cured from cancer in their

practice.

It is important to be aware that these patients are

likely to have a reduced fertility potential compared

to their counterparts in the same age group. Many

of these patients may not have had the opportunity

to receive fertility counselling before starting cancer

treatment. Some of these patients may have been

offered fertility preservation at the point of diagnosis, but may have been too overwhelmed to pursue any

definitive fertility preservation procedures.

For cancer patients who are keen to start a family,

the fertility discussion does not stop with cancer

treatment. It is equally important to continue this

conversation after treatment has been completed,

given the limited reproductive lifespan of many of

these women.

As long as premature ovarian insufficiency has not

occurred, there is still a role for fertility preservation

after cancer treatment, although pregnancy

outcomes would be expected to be inferior to that

before starting cancer treatment.

REFERENCES

Rodgers et al. The safety and efficacy of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation for fertility preservation in women with early breast cancer: a systematic review. Hum Reprod. 2017 May 1;32(5):1033-1045.

Zhu et al. Live birth rates in the first complete IVF cycle among 20 687 women using a freeze-all strategy. Hum Reprod, 2018 May 1;33(5):924-929.

Doyle et al. Successful elective and medically indicated oocyte vitrification and warming for autologous in vitro fertilization, with predicted birth probabilities for fertility preservation according to number of cryopreserved oocytes and age at retrieval. Fertil Steril. 2016 Feb;105(2):459-66.e2.

Jensen et al. Outcomes of transplantations of cryopreserved ovarian tissue to 41 women in Denmark. Hum Reprod. 2015 Dec;30(12):2838-45

Gellert et al. Transplantation of frozen-thawed ovarian tissue: an update on worldwide activity published in peer-reviewed papers and on the Danish cohort. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018 Apr;35(4):561-570.

fertility preservation in patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapy or gonadectomy: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2019 Dec;112(6):1022-1033.

Dolmans MM, Masciangelo R. Risk of transplanting malignant cells in cryopreserved ovarian tissue. Minerva Ginecol. 2018 Aug;70(4):436-443.

Blumenfeld Z. Fertility Preservation Using GnRH Agonists: Rationale, Possible Mechanisms, and Explanation of Controversy. Clin Med Insights Reprod Health. 2019 Aug 21;13:1179558119870163

Dr Serene Lim is a Consultant at Singapore General Hospital. She received her specialist

accreditation in obstetrics and gynaecology in 2015. In 2018, she was awarded the Health

Manpower Development Plan Scholarship by the Singapore Ministry of Health to pursue a

one-year fellowship in reproductive medicine and fertility preservation with Professor Kate Stern at the Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne. Dr Lim sees both general obstetrics and

gynaecology patients and has clinical interests in reproductive medicine, infertility, fertility

preservation, in-vitro fertilisation, pregnancy and labour care.

To find out more about our transplant programmes, GPs can contact the

SingHealth Duke-NUS Transplant Centre:

Tel: 6312 2720

Email: sd.transplant.centre@singhealth.com.sg