Graves’ ophthalmopathy is the most common cause of orbital disorder in adults and develops in up to 50% of patients with Graves’ disease.1 It is an autoimmune process that is progressive but self-limited, with a variable course extending over one to three years generally. Young or middle-aged women are typically affected and the orbital disease usually develops within one year from the onset of hyperthyroidism (Figure 1).2

Most Graves’ ophthalmopathy (GO) patients can be managed medically. Surgery has a specific role with regards to rehabilitation and in vision-threatening cases refractory to medical therapy.2

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF DISEASE

GO is composed of mechanical, immunological and cellular processes, each having an effect on the other in a cyclical manner. The associated histopathologic changes seen in GO are as follows: there is increased volume of the extraocular muscles, orbital connective tissue and orbital fat.3 The extraocular muscles are oedematous due to increased production of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), in particular hyaluronanic acid4 within the orbital tissue; a marked infiltration of immunocompetent cells (predominantly T lymphocytes, macrophages and to a lesser extent, B lymphocytes) is detectable.5 Infiltrating T lymphocytes are mainly T helper cells (CD4+).6

According to a widely-accepted pathogenetic hypothesis3, autoreactive T lymphocytes, recognising an antigen shared by the thyroid and the orbit, infiltrate the orbital tissue and the extraocular muscles. The TSH-receptor (TSHR) has been isolated in the orbital fibroblasts of normal individuals and patients with GO.7 The primary cellular function of fibroblasts appears to be synthesis of GAGs and enzymes necessary for GAG remodelling and degradation.8

ASSESSMENT AND TREATMENT OF THYROID EYE DISEASE

In the early stages of the condition, patients may only complain of dry eyes, eye lid swelling or puffiness. An early sign of GO is upper or lower eye lid retraction. As the condition progresses, patients can subsequently develop proptosis and a squint (from enlargement and restriction of the recti muscles) (Figure 2).

The diagnosis of GO is made from a combination of the clinical signs elicited, the results of the thyroid function tests, the thyroid autoantibodies, as well as the findings of the orbital computed tomography scan in a patient with Graves’ disease (Figure 3).

For the ophthalmic assessment of a patient with GO, it is paramount to first determine the visual function of the patient. This includes checking the visual acuity using the Snellen chart, pupillary light reflexes, colour vision and visual fields.

The clinical activity score for the patient is collated by looking at the parameters of lid swelling and injection, chemosis and conjunctival injection, caruncular swelling, pain on eye movement and pain at rest. Each of these individual parameters is given one point and if the patient has a total score of 4 or more, the inflammation in the orbit is active and the patient will be indicated for pulsed intravenous methylprednisolone therapy.

During the active phase of the disease, sight-threatening complications such as compressive optic neuropathy, glaucoma and corneal ulcers due to exposure will be actively excluded and if present, aggressively managed. When the patient enters the quiescent phase of the disease, the functional status and the cosmetic appearance of the patient will be thoroughly evaluated.

Surgical rehabilitation including orbital decompression for disfiguring proptosis, squint surgery for double vision, and eye lid surgery for lid retractions can be considered. Patients with mild disease such as dry eyes will only require ocular lubricants and conservative measures.

For the patient’s systemic control, maintenance of the euthyroid state is important to prevent progression of GO.9 Radioactive Iodine therapy may carry a small risk of the development or worsening of GO, particularly in susceptible patients.10 These adverse effects can be prevented with the concomitant administration of oral steroids.9 A threemonth course of oral prednisolone is recommended for patients with highrisk profiles.

Finally, all patients with Graves’ disease who are smokers should be strongly encouraged to stop smoking. There is strong evidence that smoking cessation is useful in the primary, secondary and tertiary prevention of Graves’ ophthalmopathy as it can profoundly influence the occurrence and the course of eye disease, and also impair its response to treatment. 11-15

WHEN TO REFER TO A SPECIALIST

Dry eyes and lid puffiness are the most common manifestations of thyroid eye disease, and can be managed expectantly or with symptomatic treatment (such as artificial tears).

However, active orbital inflammation, or moderate to severe thyroid eye disease would warrant a referral to the ophthalmologist for assessment and further treatment. Maintenance of euthyroid status and smoking cessation are important to control thyroid eye disease.

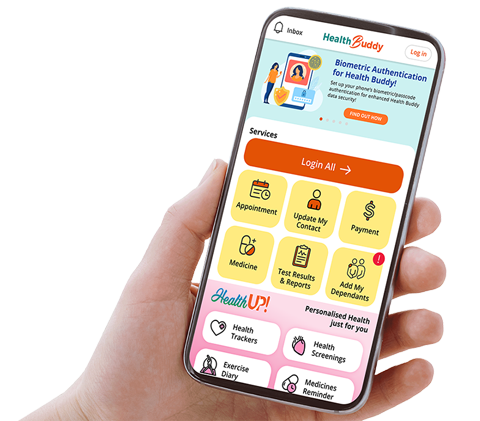

GPs can call for appointments through the GP Appointment Hotline at 6322 9399.

By: Dr Morgan Yang, Consultant, Oculoplastics Department, Singapore National Eye Centre

Dr Morgan Yang is a Consultant Ophthalmologist in the Oculoplastics Department of the Singapore National Eye Centre (SNEC). His research interests include thyroid eye disease and cytokine analysis of tears, and he is actively involved in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education.

References

1. Bahn RS, Heufelder AE. Pathogenesis of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1468–1475.

2. RL Dallow, PA Netland. Management of Thyroid-Associated Orbitopathy (Graves’ Disease). In Albert DM, Jakobiec FA (eds) The Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology. 2nd edn, pp 3082-3099. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2000.

3. Burch HB, Wartofsky L. Graves’ ophthalmopathy: current concepts regarding pathogenesis and management. Endocr Rev 1993;14:747- 793.

4. Smith TJ, Bahn RS, Gorman CA. Connective tissue, glycosaminoglycans, and diseases of the thyroid. Endocr Rev 1989;10:366-391.

5. Davies TF. Seeing T cells behind the eye. Eur J Endocrinol 1995;132:264-265.

6. Pappa A, Calder V, Ajjan R, Fells P, Ludgate M, Weetman AP, Lightman S. Analysis of extraocular muscle-infiltrating T cells in thyroidassociated ophthalmopathy (TAO). Clin Exp Immunol 1997;109:362-369.

7. Feliciello A, Porcellini A, Ciullo I, Bonavolonta G, Avvediment EV, Fenzi G. Expression of thyrotropin-receptor mRNA in healthy and Graves’ disease retro-orbital tissue. Lancet 1993;342:337–338.

8. Smith TJ. Dexamethasone regulation of glycosaminoglycan synthesis in cultured human skin fibroblasts: similar effects of glucocorticoid and thyroid hormones. J Clin Invest 1984;74:2157–2163.

9. Prummel MF et al. Effect of abnormal thyroid function on the severity of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Arch Intern Med 1990;150:1098–1101.

10. Bartalena L et al. Relation between therapy for hyperthyroidism and the course of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med 1998;338:73–78.

11. Prummel MF and Wiersinga WM. Smoking and risk of Graves’ disease. JAMA 1993;269: 479–482.

12. Hagg E, Asplund K. Is endocrine ophthalmopathy related to smoking? Br Med J 1987;295:634–635.

13. Krassas GE et al. Childhood Graves’ ophthalmopathy: results of a European questionnaire study. Eur J Endocrinol 2005;153:515–521.

14. Bartalena L, Marcocci C, Tanda ML, Manetti L, Dell’Unto E, Bartolomei MP, Nardi M, Martino E & Pinchera A. Cigarette smoking and treatment outcomes in Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Annals of Internal Medicine 1998;129:632–635.

15. Eckstein A, Quadbeck B, Mueller G, Rettenmeier AW, Hoermann R, Mann K, Steuhl P & Esser J. Impact of smoking on the response to treatment of thyroid associated ophthalmopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2004;87:773–776.

Stay Healthy With

© 2025 SingHealth Group. All Rights Reserved.